In ancient Greece, the asclepion was a healing temple dedicated to Asclepius, the God of Medicine. Asclepius learned the art of surgery from the centaur Chiron and had the ability to raise the dead. The Rod of Asclepius is a roughhewn branch entwined with a single serpent.

Monday, December 31, 2007

Happy New Year's Eve

Sunday, December 30, 2007

Amusement

There are also a few other amusing songs by them on YouTube.

Practice Questions for USMLE

More Practice Questions for USMLE

Saturday, December 29, 2007

People Like That Are The Only People Here

I read Lorrie Moore's short story, "People Like That Are The Only People Here: Canonical Babbling in Peed Onk" from her collection Birds of America (originally published in The New Yorker). This is a fantastic short story about a mother's experience in pediatric oncology. The writing style is beautiful and witty ("The Mother knows her own face is a big white dumpling of worry." "Perhaps, she thinks, she is being punished [...] she had [...] on three occasions used the formula bottle as flower vases.") Lorrie Moore captures the range and dynamics of emotion that go through a mother's head when her child is diagnosed with cancer: disbelief, guilt, bargaining (she's willing to take a car crash at age 16 if her baby is miraculously cured). The tone has a lilting quality to it; it is furious, it is pitiful, it is humorous ("All of her nutso pals stop by - the two on Prozac, the one obsessed with the word 'penis' in the word 'happiness,' the one who recently had her hair foiled green."), it is philosophical. I think there's very little good medical fiction out there, and the best comes from writers, not doctors. Lorrie Moore is an enthralling writer, and I highly suggest reading this short story.

I read Lorrie Moore's short story, "People Like That Are The Only People Here: Canonical Babbling in Peed Onk" from her collection Birds of America (originally published in The New Yorker). This is a fantastic short story about a mother's experience in pediatric oncology. The writing style is beautiful and witty ("The Mother knows her own face is a big white dumpling of worry." "Perhaps, she thinks, she is being punished [...] she had [...] on three occasions used the formula bottle as flower vases.") Lorrie Moore captures the range and dynamics of emotion that go through a mother's head when her child is diagnosed with cancer: disbelief, guilt, bargaining (she's willing to take a car crash at age 16 if her baby is miraculously cured). The tone has a lilting quality to it; it is furious, it is pitiful, it is humorous ("All of her nutso pals stop by - the two on Prozac, the one obsessed with the word 'penis' in the word 'happiness,' the one who recently had her hair foiled green."), it is philosophical. I think there's very little good medical fiction out there, and the best comes from writers, not doctors. Lorrie Moore is an enthralling writer, and I highly suggest reading this short story.Image from amazon.com, shown under fair use.

Thursday, December 27, 2007

Specialties List II

3. Emergency Medicine. Now this one is a surprise to me. I didn't come in with any draw to EM at all. But I have realized that diagnosis is extremely fun, and some of the best diagnosticians are emergency medicine physicians. There is a good mix of intellectual and procedural medicine; it can be exciting and fast paced. Although patient interaction is limited and you're nobody's "doctor," I'm not sure that would bother me too much. I like how anyone walking into an ED is treated, but there are issues with the finances of EDs. EM doctors do triage and stabilization; they are knowledgeable about much but masters of nothing, and I'm not sure I'd like that. Research possibilities are limited (it's mostly clinical). A lot of people praise the lifestyle; I'm not sure that's a big influence for me. I'm iffy on the patient population.

3. Internal Medicine -> Cardiology. I think cardiology is fascinating, and the sub-subspecialties really appeal to me (interventional, electrophysiology). It's highly competitive, well compensated, but mostly, the heart is just a great organ. The field also appeals to me as it is highly evidence-based.

4. Internal Medicine -> Hematology. This is entirely due to my classroom conception of heme; I really don't have a good idea of what hematologists do. I'm not sure I would want to do oncology, but I might end up doing the paired training anyway.

4. Pathology. I'm pretty unlikely to go this route as I love working with patients directly. However, the intellectual excitement of pathology is still quite tempting. It works well with research and teaching, two things I'm interested in. I'm no good with histology, and I'm iffy on anatomy, but I think I could find my niche somewhere (maybe ID or heme areas).

Specialties that are noticeably missing include pediatric and surgical fields. I think this is reflective of a lack of exposure to those fields; I'll figure more out later. I was originally pretty partial to opthalmology because it is fun, procedural, intellectual, well-compensated, and exportable, but I think it is too limited for me.

Wednesday, December 26, 2007

Specialties List I

1. Anesthesia -> Critical Care. I think I'd like to end up in critical care medicine because of the complexity of the cases and the emphasis on multiple organ systems and whole body physiology. That stuff excites me. I'm not entirely sure right now, but I may prefer intensive care of a patient for a limited period of time rather than a more longitudinal experience. I am okay with very sick patients who may die. I am interested in end-of-life ethics. So what about anesthesia? I think that anesthesia complements critical care well. They are both team-oriented hospital-based fields with vast possibilities of research. The procedures are similar, including hemodynamic monitoring and airway support. I like how anesthesia takes care of one person at a time, and the culture of anesthesiologists fits me well. It is an exportable specialty. Anesthesiologists work with adults, kids, pregnant women, and people in pain; it's a diverse field.

2. Internal Medicine -> Critical Care +/- Infectious Disease, Cardiology, or Pulmonary. While most people opt for a Pulmonary/Critical Care fellowship, I'm not certain that's what I'd want to do. Pulmonology doesn't excite me that much. I could consider doing infectious diseases or cardiology first. These aren't ideal pathways. ID might make sense if I'm interested in ID research or infection control (big problem in ICUs). I think it'd be a useful but not essential background. Cardiology is an iffy proposition; there was the advent of coronary care units (CCUs) but it remains to be seen whether cardiology-trained intensivists are required to run those (it may just be sufficient to have either cardiology or critical care, not both). Furthermore, I would enjoy doing a further fellowship in interventional cardiology, and to do critical care after interventional cardiology would be a significant loss in compensation (it's unlikely that I'd really care though).

The thing about critical care is that you need something else to balance it out; it's too easy to burn out doing 100% ICU medicine (if I wanted to do that, I would consider being a hospitalist). Anesthesia (well-controlled environments, one patient at a time), cardiac caths (procedural, fun, high reimbursement), pulmonary clinic (straightforward, longitudinal continuity), ID consults or infection control all provide a venue to destress. It remains to be seen what I end up choosing.

Monday, December 24, 2007

Sunday, December 23, 2007

Overdosed America

It's been a while since I wrote a book review. I had read Overdosed America by John Abramson before, but rereading it after cancer block has made it more salient. Directed at laypeople, this book argues that Americans are taking too many medications and doctors are prescribing too much because of undue influence by the pharmaceutical companies on medicine without proper independent regulatory agencies. He gives very specific examples like the often cited Vioxx/Celebrex (rofecoxib/celecoxib) drama and HRT. He does a decent job of explaining the construction and presentation of clinical studies to demonstrate how interpretation of data can be skewed to favor pharmaceutical companies (ie. using relative risk instead of absolute risk reduction). It actually made a lot of sense with epidemiology background. And I became pretty convinced that bias does creep into major studies published in journals like JAMA and NEJM. The book itself is okay. It's not groundbreaking or exceptionally written or anything. It does make a decent case, and it's pretty opinionated. But it might be worth looking at, if you're interested in the intersection between big pharma, academic medicine, and governmental regulation. It's stuff that all doctors should know, but a lot of it is presented in medical school anyway.

It's been a while since I wrote a book review. I had read Overdosed America by John Abramson before, but rereading it after cancer block has made it more salient. Directed at laypeople, this book argues that Americans are taking too many medications and doctors are prescribing too much because of undue influence by the pharmaceutical companies on medicine without proper independent regulatory agencies. He gives very specific examples like the often cited Vioxx/Celebrex (rofecoxib/celecoxib) drama and HRT. He does a decent job of explaining the construction and presentation of clinical studies to demonstrate how interpretation of data can be skewed to favor pharmaceutical companies (ie. using relative risk instead of absolute risk reduction). It actually made a lot of sense with epidemiology background. And I became pretty convinced that bias does creep into major studies published in journals like JAMA and NEJM. The book itself is okay. It's not groundbreaking or exceptionally written or anything. It does make a decent case, and it's pretty opinionated. But it might be worth looking at, if you're interested in the intersection between big pharma, academic medicine, and governmental regulation. It's stuff that all doctors should know, but a lot of it is presented in medical school anyway.

Saturday, December 22, 2007

Academic vs Community Medicine

For me, though, I think I plan on staying in academic medicine. The disadvantages are clear. The compensation is lower yet the hours may be longer; part of the salary is grant-dependent and not guaranteed. The path to promotion (and tenure) is long and difficult. Nevertheless there are many advantages. What appeals to me is the greater flexibility; I can pursue research, education, administration, and clinical activities in a proportion that best fits me. I can pick research endeavors that interest me. I also like the high intensity environment of the academic center. I would enjoy the opportunity to teach students. The decreased compensation wouldn't really bother me.

Friday, December 21, 2007

Why We Do It

"A Time That Changed My Life"

By Dante

A time that changed my life was when I entered Orange County On Track. On Track is a program that helps you with your homework and how to behave better. Also On Track teaches you how to say no to drugs, gangs, and other bad things in the world. You get mentors too that help you with stuff.

When I first entered On Track, I was very shy because I was new and I didn't know what it was about. Then, I saw that my two friends, Edgar and Jefferson, were in On Track too...We went out to play kickball-basketball. We separated into teams and started playing...After that we went into the MPR and did a lesson about not doing drugs. I answered 10 questions because I wanted stickers so I could get a cool prize. After On Track was over at 6:30 I realized how cool it was and I wanted to stay in the program.

When I finished my first year of On Track I went in the second year of On Track because I knew how good they were to us kids and they want us to make the right decisions in the present and the future.

Thursday, December 20, 2007

CBB Closure

Wednesday, December 19, 2007

Personalized Medicine

Anyway, I wanted to write a post about pharmacogenomics because it's often hailed as the next big thing in medicine. It's like testing the susceptibility of a microbe to antibiotics; you know which drugs will work best, maximizing efficacy and minimizing toxicity. I actually think this stuff is really cool and might be clinically feasible. Microarrays are a brilliant high-throughput technology, and the great hope with clinical microarrays is that we can quickly assay a patient's genotype or a cancer's profile to predict prognosis and direct treatment with more and more specificity. So although the lectures were pretty dry, I feel like this is a really cool and exciting budding field.

Tuesday, December 18, 2007

Consciousness

Monday, December 17, 2007

CAM II

It's interesting that from a philosophy standpoint, such studies may not be suitable for studying these alternative healing modalities. CAM involves a different paradigm of medicine than conventional Western science. Their view of the world and internal rules for coherence are fundamentally different than that of Western medicine. Instead of talking about enzyme kinetics and cell biology, CAM might deal with harmonizing the soul and aligning different life forces. Philosophers such as Thomas Kuhn (The Structure of Scientific Revolutions) would argue that evaluating CAM by Western standards is absurd; you can't judge a completely different system of thought with the rules of your system of thought. It's like evaluating quantum mechanics by the rules and criteria of Newtonian physics: you will get wrong answers even if it is a valid way of looking at the world. The two types of medicine are so different that they cannot be compared head-to-head.

Now to very Western thinkers, this is a ridiculous claim. Traditional science, they might say, uses objective criteria. Especially in evidence-based medicine, outcomes such as death or length of survival or recurrence of cancer are studied. These benchmarks can be used for any paradigm of health and illness. But a true Kuhnian would not be convinced. Perhaps the strength of traditional Chinese medicine is in the subjective experience of acupuncture; perhaps what's important is not the release of endorphins or the decrease in nausea and vomiting. Those are just the benefits that Western science evaluates. Unless you see the world from that paradigm, you can't predetermine how that paradigm should be evaluated. Of course, this leads to the big Kuhnian problem (which he acknowledges) that paradigms cannot be evaluated. They can only be analyzed for internal coherence, but never extrapolated to determining how close they model the world (also a very Kantian view). So it may very well be the case that both Western medicine and CAM operate to improve someone's health even though the former acts by modulating vascular reactivity to prolong survival while the latter optimizes meridians to improve the flow of Qi.

Sunday, December 16, 2007

CAM I

It's interesting. I didn't realize this was a billion dollar industry or that it has higher use in more educated populations. I learned a lot about different herbs (St. John's wort that causes major drug-drug interactions), and surprisingly (or perhaps not), many herbs that have been studied are as efficacious as traditional pharmacology in treating diseases (St. John's wort for mild-moderate depression, Kava for anxiety). We also talked about some traditional Chinese medicine (and two of our classmates had acupuncture done on them in front of the class), things I know about but never had formalized instruction in. I was especially interested to learn that in some Chinese medicine practices, the doctor is paid insofar as the patient remains healthy; only when the patient gets sick is medical attention free. It makes so much sense (the purpose of a doctor is to keep someone healthy) yet it's completely the opposite of the Western perspective. It has a much stronger orientation to preventative medicine and the whole body.

Saturday, December 15, 2007

Dean Kessler

His appointment as Dean of Medicine and Vice-Chancellor was terminated by the Chancellor J. Michael Bishop, an equally remarkable figure. I almost see this as a clash of two giants, an FDA commissioner and a Nobel Prize winner. The circumstances around this termination remain obscure and a source of rumor and gossip. Indeed, the Wikipedia page for David Kessler was updated with this news just hours after he sent out an email to the students. The situation seems to involve whistle-blowing and financial irregularities, but it's fairly complex; not only did Kessler initiate an allegation of inadequate financial controls, but an anonymous letter initiated an allegation that Kessler himself was involved in irresponsible spending. After investigation by the University auditor, neither of those allegations were substantiated.

The actual "firing" is fairly interesting. Apparently, the position of dean of the medical school is an "at-will appointment, meaning Dr. Kessler held the appointment at the pleasure of the chancellor" (UCSF Today). Evidently, this position is not protected from whistleblowing. It seems that he was offered a chance to resign and he declined, thus escalating into this termination.

I've heard Dr. Kessler speak on several occasions. He strikes me as a person who fights to the end for his principles, and will not back down until his ethical standards are met. I can't really say who is in the right here (or whether such a thing can be said), but in the capacity of dean, he has been great to us medical students, and I wish him the best of luck whatever happens next.

Thursday, December 13, 2007

Metablogging

Wednesday, December 12, 2007

Collaboration

Tuesday, December 11, 2007

Boards II

But the USMLE is also a standardized test, which I strongly dislike. I think they distort people's attitudes toward learning (learning for a test rather than for knowledge or patients). Boards don't predict how good of a doctor someone will be, but they are used by residencies to assess applicants. They don't adequately reflect the skill or knowledge base we are taught in medical school nor the skill or knowledge base a doctor needs. Of course, I recognize the limitations; there needs to be a licensing standard, and a multiple choice exam is one of the few ways that is actually feasible. It's a necessary evil.

Over this winter break, I should start studying. I have decent test taking skills, but the way I prepare is not efficient compared to many of my classmates. I strongly dislike review books, and I oppose the ridiculous commericalism surrounding standardized tests. I studied for the MCAT on my own with textbooks. But I recognize that it's hardly the best way of approaching these things.

Monday, December 10, 2007

Boards I

We recently had a talk about the Boards (and attendance doubled that of a normal lecture). I didn't find it particularly useful and got mixed messages. Some people emphasized that we're already well prepared and there is no need to start reviewing until after winter break. Others suggested that we should already have started thinking about it. The general message seemed to be that we shouldn't worry, but it is a big deal and we can't put it off either. Everything was vague, and I think it caused general anxiety.

We take Step 1 earlier than other schools, and although at this point, it feels like a disadvantage, apparently it gives us an extra elective rotation before residency applications which helps. There are rumors that UCSF "soft plays" the Boards, de-emphasizing it and that the curriculum is not geared towards the standardized test (for example, we only have lectures on five cancers: breast, cervical, lung, prostate, and skin, but the USMLE certainly expects more than that). I'm not really sure how to take all of it, but the right attitude is that here is where I am, I know what I need to do, and I have confidence I will get there come the test.

Sunday, December 09, 2007

Hematology

Surprisingly, I found benign hematology to be really fun. I wasn't expecting to; I never really thought about hematology much at all. But something to do with the intellectual aspect of it draws me. I like the differential diagnosis involved; from a blood smear (spherocytes shown above) or a few numbers like the MCV and retic count, you can get a decent impression of what might be going on (autoimmune hemolytic anemia or hereditary spherocytosis). There is a very organized way of thinking about the differential and the tests that need to be ordered. Even the coagulation cascade, which I never got for a long time, has become a little more manageable. There are just so many diseases that can involve blood, and I really enjoy thinking through them.

Surprisingly, I found benign hematology to be really fun. I wasn't expecting to; I never really thought about hematology much at all. But something to do with the intellectual aspect of it draws me. I like the differential diagnosis involved; from a blood smear (spherocytes shown above) or a few numbers like the MCV and retic count, you can get a decent impression of what might be going on (autoimmune hemolytic anemia or hereditary spherocytosis). There is a very organized way of thinking about the differential and the tests that need to be ordered. Even the coagulation cascade, which I never got for a long time, has become a little more manageable. There are just so many diseases that can involve blood, and I really enjoy thinking through them.Image shown under fair use, from the University of Virginia website.

Saturday, December 08, 2007

Another Opera

Oddly enough I saw another Puccini opera tonight - Madama Butterfly at the San Francisco Opera. It was really lovely; I think it's good for me (being fairly ignorant of such matters) to see more famous operas. Knowing the plot helped a lot. The orchestral score and singing were really beautiful, and the whole thing was very heartfelt and touching. I really enjoyed it. But now, back to studying.

Oddly enough I saw another Puccini opera tonight - Madama Butterfly at the San Francisco Opera. It was really lovely; I think it's good for me (being fairly ignorant of such matters) to see more famous operas. Knowing the plot helped a lot. The orchestral score and singing were really beautiful, and the whole thing was very heartfelt and touching. I really enjoyed it. But now, back to studying.Image is in the public domain.

Friday, December 07, 2007

Words

Thursday, December 06, 2007

Peds Preceptorships Again

Wednesday, December 05, 2007

Craig Venter's Genome

This is pretty unique. His genome is the first genome of a single identifiable individual to be published. He makes public a lot of information about himself. Indeed, people have already identified that he has a higher risk of earwax, antisocial behavior, Alzheimer's, and cardiovascular disease. His life is now an open book, and scientists are using his data to find out more about his biology. What is it like, I wonder, to find out you have a polymorphism that predisposes you to some disease? What is it like for it to be public knowledge? It's also one of those things where people find only bad things; the majority of people are looking for SNPs for disease and not ones for good hair or memory or intelligence. This seems like a very risky thing. It's really a novel and strange ethical issue.

Monday, December 03, 2007

The Gates

The Gates

The GatesRachel Hadas

No wonder we so love the dead. The living

are brittle, easily wounded,

petty, distracted by shadows,

ungrateful, obsessive, persistent,

needy, greedy, vain,

impulsive, wrapped in day's opacity.

Better at resisting

wishes, the dead are patient,

peaceable, deliberate.

Having skipped the jaws of appetite

as blithely as the pilot

who slipped the bonds of earth,

they glide across the hours.

But that I see the dead

in peaceful places, in unhurried silence

doesn't mean they're never

desperate presences

hammering at the gates.

Image is Rodin's "The Gates of Hell," Musee Rodin; from Wikipedia, GNU Free Documentation License.

Sunday, December 02, 2007

Stem Cells

The second interesting thing is the recent two articles on induced embryonic stem cells. The problem with embryonic stem cells is that the isolation is ethically controversial. In these papers, two groups (including one associated with UCSF) report a new method of generating embryonic stem cells. A differentiated adult somatic cell is transfected with a retrovirus that encodes master transcriptional regulators. These induce the differentiated cell to become undifferentiated. I took a quick look at the papers and they're very cool. The cells resemble embryonic stem cells in all the ways tested. I think this breakthrough merits further investigation, but I caution those who pay attention only to the popular press that treatments for diseases like Parkinson's or Alzheimer's are still a long way away.

Saturday, December 01, 2007

La Rondine

Even though I know very little about opera (and went with devout aficionados), I had a great time. The singing was beautiful; I was really awed by the versatility of the human voice. It was very interesting for me to realize how beauty can be expressed in a language I don't understand. I enjoyed the costuming, stage, dancing, and general ambiance. The story was easy to follow with the subtitles, but the plot was a little iffy to me (it's one of Puccini's lesser known operas). However, it was the debut of soprano Angela Gheorghiu and she was incredible. One of my friends even went to see her in Italy. I highly recommend the experience even if you're non-opera.

Image is in the public domain.

Friday, November 30, 2007

Anesthesia Shadowing

Thursday, November 29, 2007

Gratitude

When I write these Thanksgiving posts, I try to pick something very particular to focus on as I'm sure every year, there is a common battery of thanked things. This year, I'm thankful for Thanksgiving. To see friends I haven't seen for years (or year, I guess) was the happiest ever. I have ineffable gratitude for those things outside of school that allow me to maintain who I am. It's so incredibly easy to get consumed by medical school such that it becomes your identity. I'm struggling to keep my head out of that water. I'm spending more time with friends, seeing more of the city, eating at different restaurants, even reading up on more non-syllabus things (http://caseoftheday.blogspot.com/). Sometime soon, I'll start regretting this when I realize that efficiency of studying is all that counts in Boards. But right now, I'm so thankful that these things, hardly career-directed, are part of my life. The anticipation keeps me awake in lecture each day. The memories keep me warm as I'm walking back home.

Wednesday, November 28, 2007

Counterpoint: Biochem

http://bio.research.ucsc.edu/people/kellogg/contents/Demise%20of%20Bill.html

On a hill overlooking an automobile factory lived Bill, a retired geneticist, and a retired biochemist (nobody knew his name). Every morning, over a cup of coffee, and every afternoon, over a beer, they would discuss many issues and philosophical points. During their morning conversations, they would watch employees entering the automobile factory below to begin their work day. Every afternoon, as they drank their beer, they would see fully built automobiles being driven out of the other side of the factory.

Both were wholly unfamiliar with how cars worked, and they decided that they would like to learn about the functioning of cars. Having different scientific backgrounds they each took a very different approach. Bill, not being inclined towards hard work (like most geneticists), immediately came up with a scheme that he thought would lead him to an understanding of cars. The next morning he went down the hill and tied the hands of one of the workers in the factory. He then went back up the hill and sat down to have a cup of coffee. As he was just starting to sip his cup of coffee, he heard some banging noises and went out to the garage to see what was going on. When he looked in the garage he found that the biochemist had gotten one of the cars from the factory and was already covered with grease and oil as he was doing something under the hood. When Bill asked the biochemist what he was doing, he replied, "I'm taking the car apart to see how it works." The geneticist laughed out loud and then sat down to make fun of the biochemist. Bill kept telling him that he was wasting his time and that he had a much easier scheme for learning more about the functioning of cars.

Towards the end of the day, as the exhausted biochemist was washing up, the geneticist pointed to the factory below. Cars were rolling out of the factory, and each one lacked a particular circular device (the steering wheel). Moreover, each of the cars failed to make the first turn in the road as they left the factory, and all the cars were piling up on the lawn. "Hah!" exclaimed the geneticist. "The worker whose hands I tied today is responsible for installing the circular device, and the circular device is responsible for steering the car." The geneticist then asked the biochemist what he had learned that day. The biochemist said that he had been focusing on a small white object (the spark plug) and that he did not yet know what it did. The geneticist hooted with laughter.

The next day, the geneticist, emboldened by his success, went back down the hill and tied the hands of another worker. He then went back up the hill, got a cup of coffee, and sat down to another day of making fun of the biochemist. The biochemist again spent the day working in the grease and oil. At the end of the day Bill asked the biochemist what he had learned, and he replied: "I think that a component of the white object is made of an electrically conductive material, and it is surrounded by an insulator." The geneticist just chuckled. They then turned to look down the hill and noticed that there were no cars coming out of the factory. Bill seemed puzzled.

The next day the geneticist, unfazed by the puzzling result of the day before, went down the hill and tied the hands of another worker. He then went back up the hill to get a cup of coffee. As he sat down to his coffee, he heard an explosion in the garage. He ran out to see what had happened, and he found the biochemist picking himself up off the ground, his face black and most of his hair burned away. When Bill asked in amazement what had happened, the biochemist simply replied, "I have found that the liquid in the tank of the car is fairly explosive." Later that day, when they looked down at the factory to see the effect of Bill's experiment, they observed that all the cars that came out of the factory appeared to be completely normal in their function. Bill decided that the worker whose hands he had tied did nothing important for the factory.

This continued for many days. The geneticist gloated over his every discovery. For instance, at the end of one day the cars that rolled out of the factory were missing the front and rear windows, but not the side windows. Bill told the biochemist, "The worker whose hands I tied today is responsible for installing the front and back windows, and this process is independent of installing the side windows." One evening, as they were drinking some beer and arguing, the biochemist said to Bill, "Now that you have learned so much, tell me how the car works." Bill seemed puzzled by the question, but after thinking a while he said that he had noticed that whenever the cars don't have the round things (the tires) they are completely unable to go anywhere. He therefore concluded that these round things were actually responsible for moving the car. The biochemist had another sip of his beer and noticed how beautiful the sunset can be after a good day of hard work.

Meanwhile, the biochemist, after many months of hard work, thought that he was beginning to define some pathways. In one pathway, he found that the explosive liquid in the tank moved through a small pipe to a device that turned it into a vapor, and that the vapor was sucked into some cylindrical chambers. In another pathway, an electrical current flowed from a battery to the white devices he had studied earlier, and then formed a spark that ignited the explosive vapor, thus forcing the pistons out. The biochemist had also gone down the hill and taken the time to look at the cars that failed to leave the factory when Bill had tied the hands of some of the workers. He found that they were lacking carburetors, spark plugs, drive shafts, gasoline, etc. By studying these cars, he was able to confirm some of the theories that he had developed regarding the functions of the car's components.

After a while, the geneticist decided that he now knew enough about cars, and that he wanted to get one so that he could go surfing and to movies while he waited for the results of his experiments. He was running out of workers' hands to tie, so he was doing more and more elaborate experiments in which he tied several workers' hands in different combinations. In any case, he decided to get a Volkswagen Camper Van because he could fit his surfboard into it. The day he got his van, he stopped by the garage to see what nonsense the biochemist was up to. The biochemist was sitting in the car pumping the clutch, and each time he did a stream of liquid shot out from underneath the car. He told Bill that he thought the liquid in the tube leading from the clutch pedal to the clutch played a critical role in disengaging the gears from the drive shaft. Bill laughed and then drove off to spend the day at the Three Stooges Film Festival that was showing at a nearby theater.

One day Bill got in his van, but when he turned the key, nothing happened. He wasn't sure what was wrong, and he wondered whether or not his car might need new wheels. He tried the key several more times and then got out and started to walk. Pretty soon it started to rain. When he got home, the biochemist, who was drinking beer and reading James Joyce's Ulysses, asked him where he had been, and Bill told him what had happened. Bill confessed that he did not know what to do, but the biochemist said that he might be able to help. The next day they drove back to Bill's stalled van. The biochemist, not being afraid of getting his hands dirty or doing a little work, looked under the hood of Bill's van. He rapidly determined that one of the battery cables no longer made a good connection, and he had the car running in no time at all. As Bill drove away, he just shook his head.

Bill's car kept breaking down, and every time the biochemist had to go out and fix it. He tried to teach Bill how cars work, but Bill didn't seem to understand and was always more interested in his hand-tying experiments. Finally, this all came to an end when the geneticist crashed his car into a tree. Unfortunately, he was not wearing his seat belt because when he had tied the hands of the worker that installed them, the cars that came out of the factory seemed to function fine, so Bill had concluded that seat belts were vestigial and not important to the function of the car. The doctors said that Bill suffered substantial brain damage, but none of his colleagues ever noticed any difference in his behavior.

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

Point: Genetics

http://bio.research.ucsc.edu/people/sullivan/savedoug.html

On a hill overlooking an automobile factory lived Doug, a retired biochemist, and a retired geneticist (nobody knew his name). Every morning, over a cup of coffee, and every afternoon, over a glass of beer, they would discuss and argue over many issues and philosophical points. During their morning conversations, they would watch the employees entering the factory below to begin their workday. Some would be dressed in work clothes carrying a lunch pail; others, dressed in suits, would be carrying briefcases. Every afternoon, as they waited for the head on their beers to settle, they would see fully built automobiles being driven out of the other side of the factory.

Having spent a life in pursuit of higher learning, both were wholly unfamiliar with how cars worked. They decided that they would like to learn about the functioning of cars and having different scientific backgrounds they each took a very different approach. Doug immediately obtained 100 cars (he is a rich man, typical of most biochemists) and ground them up. He found that cars consist of the following; 10% glass, 25% plastic, 60% steel, and 5% other materials that he cold not easily identify. He felt satisfied that he had learned of the types and proportions of material that made up each car.

His next task was to mix these fractions to see if he could reproduce some aspect of the automobile's function. As you can imagine, this proved daunting. Doug put in long hard hours between his morning coffee and afternoon beer.

The geneticist, not being inclined toward hard work (as is true for most geneticists) pursued a less strenuous (and less expensive) approach. One day, before his morning coffee, he hiked down the hill, selected a worker at random, and tied his hands. After coffee, while the biochemist zipped up his blue jump suit, adjusted his welder's goggles, and lit his blowtorch to begin another day of grinding, the geneticist puttered around the house, made himself another pot of coffee, and browsed through the latest issue of Genetics.

That afternoon, while the automobiles were rolling off the assembly line, Doug, wet with the sweat of his day's exertions, took a sip of beer and as soon as he caught his breath began discussing his progress. "I have been focusing my efforts on a component I consistently find in the plastic fraction. It looks like this (he draws the shape of a steering wheel on the edge of a napkin). Presently I have been mixing it with the glass fraction to see if it has any activity. I am hoping that with the right mixture I may get motion, although I have not had any success so far. I believe with a bigger blow torch, perhaps even a flame thrower, I will get better results."

The geneticist was only half listening because his attention was drawn to the cars rolling off the assembly line. He noticed that they were missing the front and rear windows, but not the side windows. As soon as the biochemist finished speaking (geneticists are very polite), the geneticists proclaimed, "I have learned two facts today. The worker whose hands I tied this morning is responsible for installing car windows, and the installation of the side windows is a separate process from the installation of the front and back windows."

The following day the geneticist tied the hands of another worker. That afternoon he noticed that the cars were being produced without the plastic devices the biochemist was working on. In addition, he noticed that as the cars were being driven off to the parking lot, none of them made the first turn in the road and began piling up on the lawn.

That evening, to Doug's dismay, the geneticist concluded that steering wheels were responsible for turning the car and, in addition, that he had identified the worker responsible for installing the steering wheels.

Emboldened by his successes, the next morning the geneticist tied the hands of an individual dressed in a suit and carrying a briefcase in one hand and a laser pointer in the other (he was a vice president). That evening the geneticist and Doug (although he would not openly admit it), anxiously waited to see the effect on the cars. They speculated that the effect might be so great as to prevent the production of the cars entirely. To their surprise, however, that afternoon the cars rolled off the assembly line with no discernible effect.

The two scientists conversed late into the evening about the implications of this result. The geneticist, always having had a dislike for men in suits, concluded that the vice-president sat around drinking coffee all day (much like geneticists) and had no role in the production of the automobiles. Doug, however, held the view that there was more than one vice president so that if one was unable to perform, others could take over his duties.

The next morning Doug watched as the geneticist, in an attempt to resolve this issue, headed off towards the factory carrying a large rope to tie the hands of all the men in suits. Doug, after a slight hesitation, abandoned his goggles and blowtorch and stumbled down the hill to join him.

Monday, November 26, 2007

Thanksgiving

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

Happy Thanksgiving!

Monday, November 19, 2007

Buying Love: Big Pharma

http://medicine.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.0040150&ct=1&SESSID=cd7f9c880440d587264bcc6591a4e474

"Following the Script: How Drug Reps Make Friends and Influence Doctors" Fugh-Berman, Ahari.

Here is a related youtube video:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nj0LZZzrcrs

Sunday, November 18, 2007

Screening

Reading the syllabus sections have convinced me otherwise. There are too many factors in determining the efficacy and utility of a screening test. The best way to know if a screen works is to run a randomized control trial with mortality or morbidity as the outcome. The problem is screening has inherent biases; if you catch a disease earlier, it will appear that the person survived longer regardless of whether catching it earlier had any effect on overall outcome (if there aren't good treatments, then screening has few advantages). Screening might catch things that would not otherwise have progressed to disease (mammograms have found lots of ductal carcinoma in situ but it is unclear how many of those would have lead to invasive carcinoma).

Indeed, this is compounded by the fact that treatment for cancer is associated with morbidity and mortality. Chemotherapy is hardly benign, and a physician must really think about the oath to do no harm. The efficacy ("positive predictive value") of a screening test depends not only on its sensitivity and specificity, but also on the population prevalence of that disease. Even if a screen is extraordinarily specific for a disease, if the prevalence of that disease is very low (ie. cancer), then there will be more false positives than true positives. The utility of a screen depends also on the follow-up procedure. For example, there's a fairly good screen for ovarian cancer (transvaginal ultrasound), but the confirmatory test is surgery, and 13 oophorectomies would need to be done to find one case of ovarian cancer (compare this to 838 mammograms needed to prevent a death due to breast cancer in women 50-74). Lastly, screens must be acceptable to patients; people getting screened are healthy and the threshold for tolerating procedures varies a lot (no one wants a colonoscopy).

I was pretty surprised about all of this; it really did change my view on screening tests. Furthermore, cost-effectiveness comes into play since screens are for large populations; we need to prove that the risks we are taking (money, working up false positives, diversion of resources) are really worth the benefit. In the end, I think only cervical cancer (pap smear), breast cancer (mammogram), and colon cancer (colonoscopy or others) really meet the criteria for tests with a net benefit.

Saturday, November 17, 2007

Thursday, November 15, 2007

I love my FPC group

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

JAMA

The other thing is the section on "JAMA 100 Years Ago" which reprints articles exactly a century before. This issue's "The Laboratory in Diagnosis" was a really good read. It is searchable, but you need a license to access it online.

Tuesday, November 13, 2007

Pediatrics Preceptorship

I love children; they're fun, cute, generally healthy, curious, and excited. Most of the patients I've seen have been elementary school or younger and that demographic is just fantastic (I'm not so sure about teenagers). However, there are aspects to pediatrics (or perhaps peds EM) that I don't appreciate: the difficulty in dealing with parents who insist on antibiotics or resist vaccination, the unruly child who no one can control, the sudden mood swings and immaturity of kids trying to get their way. You also have to watch out for cases of abuse and things like that. The emergency department is interesting; it's not as scary as I would think, but it can get very busy.

Monday, November 12, 2007

Counterpoint: Biotech

Sunday, November 11, 2007

Point: Biotech

There have been many studies demonstrating the often subconscious effect of industry on physicians. Indeed, getting small gifts like pens and pads of paper have a remarkable effect on a doctor's prescribing habits even though the doctor does not realize this. In the past, biotech and big pharma had even more overt influences, offering all-expenses-paid "educational" vacations (1 hour lecture, 23 hours on the beach) or dinners at fancy restaurants in return for recruiting patients for studies. This had a detrimental effect on the objectivity of medicine and the care of the patient.

Furthermore, academic medicine and industry have to be divorced. Studies cannot be run by those with a financial (or other) conflict of interest. Studies are supposed to be objective and set the standards of care across the board; the amount of influence these journals have on medical decisions is staggering. It would be completely unethical for conflict of interests to taint such publications.

Saturday, November 10, 2007

Friday, November 09, 2007

Attendance

Thursday, November 08, 2007

U-TEACH Revisit

Wednesday, November 07, 2007

Money

This is one of those odd hypothetical questions. If someone were to give me a bolus of money (a million dollars? ten million dollars? a hundred million dollars?), I'm not sure what I would do with it. Actually, I'm pretty sure I'd do nothing with it. I'd probably pay off my loans, but I can't see myself purchasing a car or planning a vacation or buying anything extravagant. For some reason, that just doesn't occur to me. If I were particularly prudent, I would figure out how to invest the money. If I were particularly generous, I would donate. Those are things I should do. But knowing myself, I'd be strangely apathetic.

Monday, November 05, 2007

Counterpoint: Money

Even looking past the practical stuff, some people have the attitude that they deserve to be paid well. After all, doctors do amazing things. We replace heart valves, we insert tubes down your throat to breathe for you, we reattach severed body parts (I'm not sure how I got those examples, but note how they're all procedural). What we do saves lives. We train for decades to become proficient in it. We provide a service and we should let market forces dictate how much we get paid. Indeed, there are doctors turning towards "luxury boutique" medicine. For an annual retainer fee, these doctors guarantee same-day appointments, no waits, longer and more personalized care. Those doctors have fewer patient loads and much higher salaries. Someone's willing to pay an arm and a leg (or rather, they're willing to pay to keep that arm or leg), why not let them?

Sunday, November 04, 2007

Point: Money

Friday, November 02, 2007

CBB

Thursday, November 01, 2007

Wednesday, October 31, 2007

Sicko

I don't have any particular stance on for-profit versus socialized medicine paradigms of health care. What we have right now won't last, and changes need to happen. But what those are, I cannot say. I also don't have a particular stance on Michael Moore, only that the films are produced through a lens and I hope the audience recognizes that. I am glad he brought attention to this major societal issue.

Tuesday, October 30, 2007

The Spirit of Science II

"We [scientists] aspire to develop, over time, a significant, perhaps even important, body of research that approaches an interrelated set of scientific questions relevant to human physiology and disease. We realize that this takes time and that in the book of investigations we are each painstakingly putting together, there will be many chapters. Nonetheless, we anticipate that when the last chapter is done it will be possible to discern, without much difficulty, a consistent and coherent set of themes and motifs throughout the work and to understand how and why we got from here to there." I like how he orients this around scientific questions, themes, and motifs (rather than discoveries).

He makes a big point that he sees many scientists who have "bibliographies that, to be charitable, can only be referred to as miscellaneous. There is no consistent set of questions or themes: each paper relates to a different subject. Questions are not pursued in any depth. Every year or two the investigator has shifted his allegiance to the latest and trendiest subject in a very opportunistic fashion." This is a very true statement. I sometimes fear that I would succumb to such a popgun program even though I profoundly believe such an agenda doesn't deserve research support.

"We are all ultimately forced to come to grips with the realization that we are destined to never come up with the ultimate answers but rather to only be able to progressively refine the questions. In this sense, a mark of our maturity as scientists is our ability to deal with being less and less satisfied with our answers to better and better questions."

Monday, October 29, 2007

The Spirit of Science I

Sunday, October 28, 2007

Wildfire

We have a short break between I3 and the next block (cancer). I spent it at home (Orange County) where I watched with bated breath the news on the Southern California wildfires. It was incredible to me how much damage they caused and how incredibly intractable they were. With the Santa Ana winds and low humidity, it seemed like very little could be done to slow the rampage until the environmental conditions improved. It was eerie early in the week: the sky was a pale reddish-gray color, ash was swirling in the air, and everything smelled terrible. Luckily, the fires were controlled before they threatened my home. It's hard to fathom the extent and tragedy of these natural disasters. Other than that, I spent most of break catching up on sleep. We start bright and early tomorrow.

We have a short break between I3 and the next block (cancer). I spent it at home (Orange County) where I watched with bated breath the news on the Southern California wildfires. It was incredible to me how much damage they caused and how incredibly intractable they were. With the Santa Ana winds and low humidity, it seemed like very little could be done to slow the rampage until the environmental conditions improved. It was eerie early in the week: the sky was a pale reddish-gray color, ash was swirling in the air, and everything smelled terrible. Luckily, the fires were controlled before they threatened my home. It's hard to fathom the extent and tragedy of these natural disasters. Other than that, I spent most of break catching up on sleep. We start bright and early tomorrow.Image is from Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

Saturday, October 27, 2007

I3

Friday, October 26, 2007

Global Health

(Capitol Steps - "TB on a Jet Plane" to the tune of "Leaving on a Jet Plane")

The I3 block had a module on epidemiology, public health, and global health. The epidemiology was a little dry but necessary; we learned about the structures of clinical studies (cohorts, cross-sectional, case-control, etc.). I'm not super interested in running clinical studies, but I actually like learning about the theory behind different study structures, their strengths and weaknesses. The public and international health made sense in the context of infectious diseases. It also isn't one of my particular interests, but I was glad to get a little exposure to how the public health system works and what happens if another SARS (or TB) incident occurs.

Thursday, October 25, 2007

Pelvic

I had a good experience with the female pelvic. Interestingly, the patient educator was doing a PhD in sex and culture (or something like that. I also heard another one of the female instructors was a "clinical sexologist"). For some reason, I found it fascinating to actually see internal organs "noninvasively" (I guess that term is iffy for those who've actually had a speculum inserted). But seeing the cervical os was cool. You realize that Netter's two-dimensional drawings don't quite capture the three-dimensional anatomy. I was also able to feel both ovaries and the top of the uterus in the bimanual exam, which was great; I'm always worried I can't palpate things (especially if I go into something procedural). I guess this experience stops me from automatically crossing OB/GYN from the list, but it's still kind of unlikely.

Wednesday, October 24, 2007

Chagas

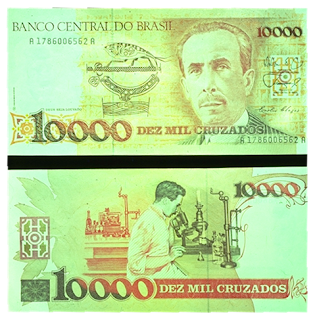

I really like these images of Brazilian currency. They have a portrait of a scientist on them! Carlos Chagas was a Brazilian microbiologist and doctor who described Chagas' disease, a really common parasitic infection of South America and a leading cause of cardiac disease there. It just seems so cool to me that a scientist rather than a politician is printed on money. Furthermore, the second image shows the actual life cycle of Trypanosoma cruzi (the causative agent). I like it much better than pyramids and eyes and eagles. If you look closely enough, you can see the reduviid bug infected with the parasites biting into the skin. The parasites are actually deposited in the feces (that's the circular blob at the back of the bug) and introduced into the bloodstream that way. The bottom of the image shows the parasites living in cardiac muscle with its fibers. Cool stuff! I wonder if you can cheat on an exam by looking at your money.

I really like these images of Brazilian currency. They have a portrait of a scientist on them! Carlos Chagas was a Brazilian microbiologist and doctor who described Chagas' disease, a really common parasitic infection of South America and a leading cause of cardiac disease there. It just seems so cool to me that a scientist rather than a politician is printed on money. Furthermore, the second image shows the actual life cycle of Trypanosoma cruzi (the causative agent). I like it much better than pyramids and eyes and eagles. If you look closely enough, you can see the reduviid bug infected with the parasites biting into the skin. The parasites are actually deposited in the feces (that's the circular blob at the back of the bug) and introduced into the bloodstream that way. The bottom of the image shows the parasites living in cardiac muscle with its fibers. Cool stuff! I wonder if you can cheat on an exam by looking at your money.

Tuesday, October 23, 2007

Parasites

Monday, October 22, 2007

Bishop

Saturday, October 20, 2007

300

Friday, October 19, 2007

On Marriage

"Friends from the old days tell me that at some point in my life, I professed that I should never marry. If this is the case, then I must remind readers that I am the consummate Emma: it is likely that my ignorance of my own emotions is only rivaled by my presumption of omniscience on the same score." (RN)

Thursday, October 18, 2007

ASA III

Afterwards, there was a reception sponsored by biotech. Lots of up-and-coming anesthesiologists (many residents and fellows). I hung out with some of the other medical students (who were all worried about missing massive amounts of class). The food and venue were excellent. In sum, it was a fun and educational experience, though it took up a lot of my time.

Wednesday, October 17, 2007

ASA II

I also heard several talks and panels. Interestingly, one research talk was by a woman who is a rival to my old lab at Stanford, so I knew a whole lot about her research and who she was. I attended a panel on medical student and resident education which I found worthwhile. I like these kinds of sessions, but it's pretty passive learning.

Monday, October 15, 2007

ASA I

Sunday, October 14, 2007

Health and Consumerism

I have talked to several doctors about this phenomenon. Now, patients will come in with a printout from the internet, sure they know what they have. There are lots of websites out there where you can input your symptoms and get back a diagnosis. As you may expect, not all of them are good. Patients will claim they have things like fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome, clinical entities that aren't clearly defined and a diagnosis of exclusion. Chances are, they don't have it. But they're sure they do.

On the one hand, health awareness is important. Medicine should not be some black box science that only doctors can interpret. But bad sources of information are bad. Much of an office visit now consists of convincing a patient that his or her self diagnosis may not be right. Indeed, at my last preceptorship, a woman brought in a photocopy of an entry on polymyalgia rheumatica from the Merck manual. Neither my preceptor nor I thought she had it, but we had to concede to running a sed rate to convince her. I think knowing too much about too little impedes efficient healthcare.

Furthermore, if Google or Microsoft starts giving curbside consults (or rather online consults), no matter how good the search algorithm or how complete the library of knowledge, I think it is too dangerous. Patients will demand tests and treatments that are neither indicated nor cost effective. They will challenge medical decisions made by physicians based on internet resources. This is not a good direction for medicine. If doctors could be supplanted by a computer search, we'd already be gone.

Saturday, October 13, 2007

Online Health Records

When the Google announcement came out on this, I made a note to blog about it, but I'm only coming around to it now. Both Google and Microsoft have been working on online health records; I'm most familiar with the news around Google health. The information storage program would allow consumers to make available, access, and organize health related data: medications, allergies, past medical history, family history, immunizations, test results, and basic information like age/sex/height.

It is clear that electronic health records are superior to paper records, leading to better outcomes and fewer mistakes, yet hospitals are having trouble switching to computerized databases. Furthermore, there may not be compatibility between different systems; if a patient moves from one state to another, their health records may or may not follow them. An online information health record like Google or Microsoft's may smooth out the transition for health care systems to move into electronic records.

However, after talking to a number of people, I have begun to develop reservations regarding consumer-controlled online health records. First is the issue of privacy. Obviously there can be a lot of problems if private information gets inadvertently released to parties who shouldn't have access. But there are other implications. If you had a psychiatric diagnosis that you didn't want anyone to know, you might not put it in the online database. But that means the online health record is incomplete and loses its power. This would favor hospital-based internal health records over public consumer-controlled online health databases. Furthermore, if patients can change what they have on the file, everything must be taken with a grain of salt. A patient's idea of a migraine may be very different than a clinical diagnosis of one. Everything will be in the consumer's control, and I am unsure that is the most prudent decision for something as complex as a health record.

Image from http://googlesystem.blogspot.com/2007/08/google-health-prototype.html