I watched Michael Moore's documentary SiCKO on the health care industry. He is very good at what he does: laying out in stark relief the issue which he's trying to tackle. He's also very good at entertaining, and to those goals, the documentary is great. I liked it, and I saw how much contrast he was able to draw out of the health care systems of the U.S. and France or Cuba or Great Britain. But it's very difficult to tease out how much is "real" and how much is good media persuasion (while all the facts may be true facts, they may not be a realistic portrayal of the entire situation). When you watch films like this, you can't let his potent documentary tactics steamroll you with his agenda. I guess trained as a scientist and philosopher, I find anecdotal evidence very circumstantial. You can get horror stories about most any industry; these stories are sad but don't convince me very much. Yet giving this problem a face propels the agenda forward in this movie, and that's what Michael Moore is good at. The other thing is that this is an entirely one-sided argument. The movie is able to get away with tons of fallacies: straw man argument, biased samples, generalizations, package-deal fallacy, problems of induction, Ad hominem attacks. From an argumentative standpoint, it's ridiculous. But it's sensational.

I don't have any particular stance on for-profit versus socialized medicine paradigms of health care. What we have right now won't last, and changes need to happen. But what those are, I cannot say. I also don't have a particular stance on Michael Moore, only that the films are produced through a lens and I hope the audience recognizes that. I am glad he brought attention to this major societal issue.

Wednesday, October 31, 2007

Tuesday, October 30, 2007

The Spirit of Science II

Here are a few more quotes from Lefkowitz's speech that I really like.

"We [scientists] aspire to develop, over time, a significant, perhaps even important, body of research that approaches an interrelated set of scientific questions relevant to human physiology and disease. We realize that this takes time and that in the book of investigations we are each painstakingly putting together, there will be many chapters. Nonetheless, we anticipate that when the last chapter is done it will be possible to discern, without much difficulty, a consistent and coherent set of themes and motifs throughout the work and to understand how and why we got from here to there." I like how he orients this around scientific questions, themes, and motifs (rather than discoveries).

He makes a big point that he sees many scientists who have "bibliographies that, to be charitable, can only be referred to as miscellaneous. There is no consistent set of questions or themes: each paper relates to a different subject. Questions are not pursued in any depth. Every year or two the investigator has shifted his allegiance to the latest and trendiest subject in a very opportunistic fashion." This is a very true statement. I sometimes fear that I would succumb to such a popgun program even though I profoundly believe such an agenda doesn't deserve research support.

"We are all ultimately forced to come to grips with the realization that we are destined to never come up with the ultimate answers but rather to only be able to progressively refine the questions. In this sense, a mark of our maturity as scientists is our ability to deal with being less and less satisfied with our answers to better and better questions."

"We [scientists] aspire to develop, over time, a significant, perhaps even important, body of research that approaches an interrelated set of scientific questions relevant to human physiology and disease. We realize that this takes time and that in the book of investigations we are each painstakingly putting together, there will be many chapters. Nonetheless, we anticipate that when the last chapter is done it will be possible to discern, without much difficulty, a consistent and coherent set of themes and motifs throughout the work and to understand how and why we got from here to there." I like how he orients this around scientific questions, themes, and motifs (rather than discoveries).

He makes a big point that he sees many scientists who have "bibliographies that, to be charitable, can only be referred to as miscellaneous. There is no consistent set of questions or themes: each paper relates to a different subject. Questions are not pursued in any depth. Every year or two the investigator has shifted his allegiance to the latest and trendiest subject in a very opportunistic fashion." This is a very true statement. I sometimes fear that I would succumb to such a popgun program even though I profoundly believe such an agenda doesn't deserve research support.

"We are all ultimately forced to come to grips with the realization that we are destined to never come up with the ultimate answers but rather to only be able to progressively refine the questions. In this sense, a mark of our maturity as scientists is our ability to deal with being less and less satisfied with our answers to better and better questions."

Monday, October 29, 2007

The Spirit of Science I

I was reading a speech by Robert Lefkowitz to the American Society of Clinical Investigation entitled "The Spirit of Science." He argues that the spirit of science has three main elements: enthusiasm, creativity, and integrity. "True enthusiasm for what we do, a real passion for new knowledge, is an empowering trait. It confers the ability, or rather the willingness, to tackle difficult and challenging problems." As for creativity, he claims that unexpected insights and curious intuitions play a pivotal role in the framework of the scientific method and cool, clear-headed logic. We need to let this synergistic action guide our studies. "It is, in fact, from the fresh minds of our least experienced students and fellows, who are unencumbered by the dogmas and paradigms of our particular fields, that the most innovative and intuitive ideas are likely to spring, for it is they who are most likely to question assumptions that we have long ago accepted." He says that "luck in science is little more than the cumulative effects of intuition, creativity, and serendipity [which is] the gift of finding valuable things that are not specifically sought." This of course refers to the often described experience where data is unexpected and a researcher investigates further, eventually making some groundbreaking discovery. Lastly, Lefkowitz acknolwedges the importance of integrity, "an unswerving commitment to what we perceive as true and right, and to a set of consistent, personally realized principles of action." I really like what he writes (I also like him as a person), and often think about it with relation to whether science is what I want to pursue in life.

Sunday, October 28, 2007

Wildfire

We have a short break between I3 and the next block (cancer). I spent it at home (Orange County) where I watched with bated breath the news on the Southern California wildfires. It was incredible to me how much damage they caused and how incredibly intractable they were. With the Santa Ana winds and low humidity, it seemed like very little could be done to slow the rampage until the environmental conditions improved. It was eerie early in the week: the sky was a pale reddish-gray color, ash was swirling in the air, and everything smelled terrible. Luckily, the fires were controlled before they threatened my home. It's hard to fathom the extent and tragedy of these natural disasters. Other than that, I spent most of break catching up on sleep. We start bright and early tomorrow.

We have a short break between I3 and the next block (cancer). I spent it at home (Orange County) where I watched with bated breath the news on the Southern California wildfires. It was incredible to me how much damage they caused and how incredibly intractable they were. With the Santa Ana winds and low humidity, it seemed like very little could be done to slow the rampage until the environmental conditions improved. It was eerie early in the week: the sky was a pale reddish-gray color, ash was swirling in the air, and everything smelled terrible. Luckily, the fires were controlled before they threatened my home. It's hard to fathom the extent and tragedy of these natural disasters. Other than that, I spent most of break catching up on sleep. We start bright and early tomorrow.Image is from Wikipedia and is in the public domain.

Saturday, October 27, 2007

I3

In sum, I3 was a fun and interesting block. Although a lot of the time, it felt like rote memorization of microbes, once I started getting familiar with them, the material became pretty accessible. I felt that a lot of what we learned will be important no matter what specialty we go into, and it was good to learn in detail about diseases I'd heard before but never really understood (like strep throat). We looked at unusual diseases carried by ticks and mosquitoes or caused by fungi and protozoa. I liked the detective nature of it, using clues about epidemiology, biochemistry, location of infection, etc. to make inferences about the causative organism. The labs weren't bad, and we had a lot of case-based learning. We also reviewed basic immunology, rheumatology, epidemiology, public health, and global health. The block wasn't incredibly well organized, and the syllabus had a lot of annoying typographical errors, but the material was pretty solid. I like how infectious disease involves all the organ systems of the body in many different disease states. I also like how potent vaccines are in reducing or eliminating disease.

Friday, October 26, 2007

Global Health

"You brought TB on a jet plane, / and it's a drug resistant strain. / How could they let you go? / Your new daddy works for the CDC / and he said it's alright by me / don't worry, go and have your wedding day. / But nobody dreamed the gift you brung / would get on board inside your lung / and TSA took my Purell away..."

(Capitol Steps - "TB on a Jet Plane" to the tune of "Leaving on a Jet Plane")

The I3 block had a module on epidemiology, public health, and global health. The epidemiology was a little dry but necessary; we learned about the structures of clinical studies (cohorts, cross-sectional, case-control, etc.). I'm not super interested in running clinical studies, but I actually like learning about the theory behind different study structures, their strengths and weaknesses. The public and international health made sense in the context of infectious diseases. It also isn't one of my particular interests, but I was glad to get a little exposure to how the public health system works and what happens if another SARS (or TB) incident occurs.

(Capitol Steps - "TB on a Jet Plane" to the tune of "Leaving on a Jet Plane")

The I3 block had a module on epidemiology, public health, and global health. The epidemiology was a little dry but necessary; we learned about the structures of clinical studies (cohorts, cross-sectional, case-control, etc.). I'm not super interested in running clinical studies, but I actually like learning about the theory behind different study structures, their strengths and weaknesses. The public and international health made sense in the context of infectious diseases. It also isn't one of my particular interests, but I was glad to get a little exposure to how the public health system works and what happens if another SARS (or TB) incident occurs.

Thursday, October 25, 2007

Pelvic

We recently learned to do the male and female pelvic exams. We were in pairs with trained patient educators, and it was a really good experience. It wasn't awkward, and the instructors were very good at putting us at ease, maintaining a professional distance yet also understanding that we were learning all of this for the first time. I had my male exam first where I learned the infamous cremaster reflex and felt a prostate (not a favorite thing to do). It was a little frustrating since the patient educator took a really slow pace, doing everything by the book. But I learned the exam pretty well so it was okay. It's highly unlikely I'll go into something like urology or colorectal surgery (but who knows?)

I had a good experience with the female pelvic. Interestingly, the patient educator was doing a PhD in sex and culture (or something like that. I also heard another one of the female instructors was a "clinical sexologist"). For some reason, I found it fascinating to actually see internal organs "noninvasively" (I guess that term is iffy for those who've actually had a speculum inserted). But seeing the cervical os was cool. You realize that Netter's two-dimensional drawings don't quite capture the three-dimensional anatomy. I was also able to feel both ovaries and the top of the uterus in the bimanual exam, which was great; I'm always worried I can't palpate things (especially if I go into something procedural). I guess this experience stops me from automatically crossing OB/GYN from the list, but it's still kind of unlikely.

I had a good experience with the female pelvic. Interestingly, the patient educator was doing a PhD in sex and culture (or something like that. I also heard another one of the female instructors was a "clinical sexologist"). For some reason, I found it fascinating to actually see internal organs "noninvasively" (I guess that term is iffy for those who've actually had a speculum inserted). But seeing the cervical os was cool. You realize that Netter's two-dimensional drawings don't quite capture the three-dimensional anatomy. I was also able to feel both ovaries and the top of the uterus in the bimanual exam, which was great; I'm always worried I can't palpate things (especially if I go into something procedural). I guess this experience stops me from automatically crossing OB/GYN from the list, but it's still kind of unlikely.

Wednesday, October 24, 2007

Chagas

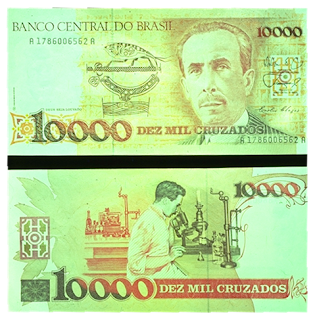

I really like these images of Brazilian currency. They have a portrait of a scientist on them! Carlos Chagas was a Brazilian microbiologist and doctor who described Chagas' disease, a really common parasitic infection of South America and a leading cause of cardiac disease there. It just seems so cool to me that a scientist rather than a politician is printed on money. Furthermore, the second image shows the actual life cycle of Trypanosoma cruzi (the causative agent). I like it much better than pyramids and eyes and eagles. If you look closely enough, you can see the reduviid bug infected with the parasites biting into the skin. The parasites are actually deposited in the feces (that's the circular blob at the back of the bug) and introduced into the bloodstream that way. The bottom of the image shows the parasites living in cardiac muscle with its fibers. Cool stuff! I wonder if you can cheat on an exam by looking at your money.

I really like these images of Brazilian currency. They have a portrait of a scientist on them! Carlos Chagas was a Brazilian microbiologist and doctor who described Chagas' disease, a really common parasitic infection of South America and a leading cause of cardiac disease there. It just seems so cool to me that a scientist rather than a politician is printed on money. Furthermore, the second image shows the actual life cycle of Trypanosoma cruzi (the causative agent). I like it much better than pyramids and eyes and eagles. If you look closely enough, you can see the reduviid bug infected with the parasites biting into the skin. The parasites are actually deposited in the feces (that's the circular blob at the back of the bug) and introduced into the bloodstream that way. The bottom of the image shows the parasites living in cardiac muscle with its fibers. Cool stuff! I wonder if you can cheat on an exam by looking at your money.

Tuesday, October 23, 2007

Parasites

In the last week of I3, we covered a lot of different parasites. It was both interesting and disturbing. I didn't know that parasites had such a huge global burden; malaria and helminths (worms) are incredibly widespread, especially in the developing world. In any case, I'm not sure I could be a parasitologist. Learning about the different protozoa and cysts and hookworms and pinworms in our environment and foods - it was a little too much for me. I suppose now I might think twice before eating sushi or pork. But hopefully that'll pass; I have to remind myself that these diseases which sound grotesque and disgusting from a lay standpoint are often less severe than bacterial and viral illnesses that don't give us pause because we can't imagine what the organisms look like. The other interesting thing is the high number of parasite cases in the TV show House. It makes sense; these diseases are exotic and strange and unique. Even the first episode of the first season had neurocysticercosis.

Monday, October 22, 2007

Bishop

We got several lectures by J. Michael Bishop who won the 1989 Nobel for his work on retroviral oncogenes. He and Harold Varmus discovered the first oncogene V-Src. Indeed, in his lecture, he once commented on the "Nobeligenic enzyme reverse transcriptase." He is an active professor and the Chancellor here at UCSF (though I cannot tell you exactly what that entails). Getting lectures from him on viruses that cause cancer, arboviruses, hepatitis viruses, and others was such a treat. He is an amazing storyteller who draws out the history of these diseases to make them salient. True, we'll never be tested on who Walter Reed was and what he did with Yellow Fever. But hearing him tell the story really puts science and discovery in a historical context. He's also very approachable and engaging, and I can't help but be in awe. He reminds me of Douglas Osheroff who won the 1996 Physics for superfluidity and who gives freshman physics lectures at Stanford. I've heard him talk several times. People this brilliant and this accessible really inspire me to pursue great things.

Saturday, October 20, 2007

300

One of my short story teachers once told me that being a writer is hard. It's easy to be a student who writes or a chef who writes or an accountant who writes. But being a writer qua writer is excruciatingly difficult. This is why I try to blog every day. I want to produce something, to actually generate something. Otherwise, I find myself sitting too much in lecture, reading too much from books. There's something extremely pleasurable in crafting something, and being an artless person, I can only turn to words as a vehicle for ideas. I'm still a med student who blogs. But I'm working to become, someday, a student and a writer such that both aspects play an equal role in how I define myself.

Friday, October 19, 2007

On Marriage

This quotable quote is from a friend. I really like it and how its written.

"Friends from the old days tell me that at some point in my life, I professed that I should never marry. If this is the case, then I must remind readers that I am the consummate Emma: it is likely that my ignorance of my own emotions is only rivaled by my presumption of omniscience on the same score." (RN)

"Friends from the old days tell me that at some point in my life, I professed that I should never marry. If this is the case, then I must remind readers that I am the consummate Emma: it is likely that my ignorance of my own emotions is only rivaled by my presumption of omniscience on the same score." (RN)

Thursday, October 18, 2007

ASA III

For my summer project, I was required to do a poster and a 5 minute powerpoint presentation at the ASA. It wasn't too bad. Making the poster took a while; I get really obsessive-compulsive about having everything line up evenly and look pretty. The poster session was okay; there were all the medical students of that research program and a bunch of their mentors. But there were also random MDs wandering around asking us about our research, which was kind of cool. I met a bunch of medical students from all over the country. The range of research went from education and patient safety to clinical cohort studies and basic science. A subset of us then did 5-minute powerpoint presentations followed by a few questions. It went fine; I had done decent preparation and talked to the moderator beforehand so I had a good idea of the question he would ask. The experience was excellent; it was a fairly large room with a decent number of people (and luckily, few experts in the field). I like listening to other presentations. I have to admit, I pay as much attention to the delivery as I do to the content. It's a good way of learning what techniques work.

Afterwards, there was a reception sponsored by biotech. Lots of up-and-coming anesthesiologists (many residents and fellows). I hung out with some of the other medical students (who were all worried about missing massive amounts of class). The food and venue were excellent. In sum, it was a fun and educational experience, though it took up a lot of my time.

Afterwards, there was a reception sponsored by biotech. Lots of up-and-coming anesthesiologists (many residents and fellows). I hung out with some of the other medical students (who were all worried about missing massive amounts of class). The food and venue were excellent. In sum, it was a fun and educational experience, though it took up a lot of my time.

Wednesday, October 17, 2007

ASA II

I spent a good amount of time in the exhibit hall of the conference which was mostly occupied by industry. I realize all the evidence on how industry influences physicians, but that will be the topic of a future post. I did pick up some free gifts, and I have to admit, they keep getting fancier and fancier (a USB drive? engraved penlight?). But, the really cool stuff was playing with some of the new biotech toys. Since it was an anesthesiology conference, there were a ton of biotech booths hawking new equipment for intubation and other procedures. I got to use a fiberoptic camera endotracheal tube, which was fun. The industry guy walked me through how to use the MAC blade, visualize the uvula, snake the endotracheal tube through, and use the fiberoptic camera to visualize the vocal cords. I'm sure though, the model was anatomically structured to be extra easy to make the product look good. I also got to do a fake lumbar puncture, and I learned about some new anesthetics (or new formulations of old anesthetics). The absolutely best way, though, to keep a crowd around a biotech booth is with a magician. It was ridiculous. The guy was an incredibly good showman (of course the magic word was the product they were trying to sell) and he performed some very impressive tricks. It's pretty hard to keep a crowd of rational, disbelieving doctors captivated.

I also heard several talks and panels. Interestingly, one research talk was by a woman who is a rival to my old lab at Stanford, so I knew a whole lot about her research and who she was. I attended a panel on medical student and resident education which I found worthwhile. I like these kinds of sessions, but it's pretty passive learning.

I also heard several talks and panels. Interestingly, one research talk was by a woman who is a rival to my old lab at Stanford, so I knew a whole lot about her research and who she was. I attended a panel on medical student and resident education which I found worthwhile. I like these kinds of sessions, but it's pretty passive learning.

Monday, October 15, 2007

ASA I

The past few days I've been spending most of my time at the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) annual meeting which is downtown San Francisco at the Moscone Center (so not that exciting, but I guess it means I don't miss any class). My summer research project was sponsored by a foundation associated with the ASA so all of us are invited to present our research (more on that later). Anyway, I am a little spoiled because I frequent conferences, something that I really need to thank my old mentor for. I learn a lot just being at a conference and seeing what issues are controversial, what new ideas are on the forefront of knowledge, and what technologies are being developed. From basic science to clinical medicine to bioethics to policy to education, I can always find something remotely interesting and comprehensible. It's inspiring. I get a better idea of what being an anesthesiologist means. It also amuses me to see hundreds of anesthesiologists milling about. I like hearing and meeting the pioneers of the specialty and brilliant researchers and master clinicians. Things are very busy; I am still scrambling to put together a presentation for tomorrow, and I'm starting to get a little worried about the final exam on Monday as I might not get a chance to pick up the syllabus until all this commotion is over.

Sunday, October 14, 2007

Health and Consumerism

The other thing about Google or Microsoft health (yesterday's post) is that the websites may make medical suggestions to the user based on information it has. This is simply an extension of Google's incredibly powerful personalized advertisement system. It is also an extension of the accessibility of health information.

I have talked to several doctors about this phenomenon. Now, patients will come in with a printout from the internet, sure they know what they have. There are lots of websites out there where you can input your symptoms and get back a diagnosis. As you may expect, not all of them are good. Patients will claim they have things like fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome, clinical entities that aren't clearly defined and a diagnosis of exclusion. Chances are, they don't have it. But they're sure they do.

On the one hand, health awareness is important. Medicine should not be some black box science that only doctors can interpret. But bad sources of information are bad. Much of an office visit now consists of convincing a patient that his or her self diagnosis may not be right. Indeed, at my last preceptorship, a woman brought in a photocopy of an entry on polymyalgia rheumatica from the Merck manual. Neither my preceptor nor I thought she had it, but we had to concede to running a sed rate to convince her. I think knowing too much about too little impedes efficient healthcare.

Furthermore, if Google or Microsoft starts giving curbside consults (or rather online consults), no matter how good the search algorithm or how complete the library of knowledge, I think it is too dangerous. Patients will demand tests and treatments that are neither indicated nor cost effective. They will challenge medical decisions made by physicians based on internet resources. This is not a good direction for medicine. If doctors could be supplanted by a computer search, we'd already be gone.

I have talked to several doctors about this phenomenon. Now, patients will come in with a printout from the internet, sure they know what they have. There are lots of websites out there where you can input your symptoms and get back a diagnosis. As you may expect, not all of them are good. Patients will claim they have things like fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue syndrome, clinical entities that aren't clearly defined and a diagnosis of exclusion. Chances are, they don't have it. But they're sure they do.

On the one hand, health awareness is important. Medicine should not be some black box science that only doctors can interpret. But bad sources of information are bad. Much of an office visit now consists of convincing a patient that his or her self diagnosis may not be right. Indeed, at my last preceptorship, a woman brought in a photocopy of an entry on polymyalgia rheumatica from the Merck manual. Neither my preceptor nor I thought she had it, but we had to concede to running a sed rate to convince her. I think knowing too much about too little impedes efficient healthcare.

Furthermore, if Google or Microsoft starts giving curbside consults (or rather online consults), no matter how good the search algorithm or how complete the library of knowledge, I think it is too dangerous. Patients will demand tests and treatments that are neither indicated nor cost effective. They will challenge medical decisions made by physicians based on internet resources. This is not a good direction for medicine. If doctors could be supplanted by a computer search, we'd already be gone.

Saturday, October 13, 2007

Online Health Records

When the Google announcement came out on this, I made a note to blog about it, but I'm only coming around to it now. Both Google and Microsoft have been working on online health records; I'm most familiar with the news around Google health. The information storage program would allow consumers to make available, access, and organize health related data: medications, allergies, past medical history, family history, immunizations, test results, and basic information like age/sex/height.

It is clear that electronic health records are superior to paper records, leading to better outcomes and fewer mistakes, yet hospitals are having trouble switching to computerized databases. Furthermore, there may not be compatibility between different systems; if a patient moves from one state to another, their health records may or may not follow them. An online information health record like Google or Microsoft's may smooth out the transition for health care systems to move into electronic records.

However, after talking to a number of people, I have begun to develop reservations regarding consumer-controlled online health records. First is the issue of privacy. Obviously there can be a lot of problems if private information gets inadvertently released to parties who shouldn't have access. But there are other implications. If you had a psychiatric diagnosis that you didn't want anyone to know, you might not put it in the online database. But that means the online health record is incomplete and loses its power. This would favor hospital-based internal health records over public consumer-controlled online health databases. Furthermore, if patients can change what they have on the file, everything must be taken with a grain of salt. A patient's idea of a migraine may be very different than a clinical diagnosis of one. Everything will be in the consumer's control, and I am unsure that is the most prudent decision for something as complex as a health record.

Image from http://googlesystem.blogspot.com/2007/08/google-health-prototype.html

Friday, October 12, 2007

Rage

In FPC, we had a standardized patient playing the role of Rage, a homeless 17 year old presenting with pain on urination. She was a difficult patient. She did not make eye contact or shake my hand, shouted profanity and banged on the walls. When I first started talking to her, she repeated everything I said back to me like an 8 year old. She played with her gum, making obscene shapes and commenting on it. When asked how many sexual partners she had, she said "a bajillion." She then started hitting on me. When I asked her whether she smoked marijuana, she asked me if I did. When I said no, she told me I was really missing out and that she had some pot and we could get high together. I couldn't get much information from her, and what I did get, I couldn't be certain was true.

It was a really hard interview. I thought I'd be decent at it, but I was wrong. I became irritated (maybe even angry) and I took it out on the patient, becoming authoritarian and even sarcastic rather than empathetic and calm. I felt like I was distancing her, and that her responses of "Yeah, whatever" were simply to placate me. She had all these tools in her arsenal: judging me, being obnoxious, blackmail, coercion, eliciting pity, manipulation. It was very hard for me not to respond in like.

I am not sure how I should have handled the situation or whether any other tactic would have worked better for me. Indeed, my classmates took different strategies: being more passive and playing the role of a peer or playing on her goals and fears in life. But each attempt to communicate with this laconic, emotionally closed, uncooperative patient had its strengths and weaknesses. All in all, this was an excellent exercise in learning to deal with adolescents and all the psychosocial and behavioral issues that come with them. I learned a lot from my supportive classmates; hopefully when I see a real patient in this sort of situation, I will have a better idea of how to proceed.

It was a really hard interview. I thought I'd be decent at it, but I was wrong. I became irritated (maybe even angry) and I took it out on the patient, becoming authoritarian and even sarcastic rather than empathetic and calm. I felt like I was distancing her, and that her responses of "Yeah, whatever" were simply to placate me. She had all these tools in her arsenal: judging me, being obnoxious, blackmail, coercion, eliciting pity, manipulation. It was very hard for me not to respond in like.

I am not sure how I should have handled the situation or whether any other tactic would have worked better for me. Indeed, my classmates took different strategies: being more passive and playing the role of a peer or playing on her goals and fears in life. But each attempt to communicate with this laconic, emotionally closed, uncooperative patient had its strengths and weaknesses. All in all, this was an excellent exercise in learning to deal with adolescents and all the psychosocial and behavioral issues that come with them. I learned a lot from my supportive classmates; hopefully when I see a real patient in this sort of situation, I will have a better idea of how to proceed.

Thursday, October 11, 2007

Writer's Group

I attend the writer's group, a bunch of medical students who are interested in creative writing (mostly fiction). It's fun, we usually hang out at someone's place and workshop stories or poems. I really miss structured creative writing workshops from undergrad, so this is nice. It's not the easiest thing to keep up with though, since everyone is so busy. Recently, we worked with David Watts who is an MD and a writer. I love talking to actual writers about their ideas, techniques, and tricks of the trade. He wrote the book Bedside Manners and is a commentator on NPR. It's inspiring to hear him talk about the art and practice of writing.

Tuesday, October 09, 2007

Preceptorship

Today was my last adult preceptorship. I've really enjoyed working with my preceptor, an internal medicine doctor in a nursing home setting. It's an odd feeling, leaving this clinic for the final time, not knowing what will happen to the patients I saw today. Someone struggling with metastatic cancer to the bone, someone self-diagnosing polymyalgia rheumatica, someone trying to figure out the right combination of medications for CHF. These people were kind enough to let me peek into their lives, ask them personal questions, and hazard an attempt at the physical examination. I got a glimpse of patients two generations older than me, facing health concerns of devastating gravity and seriousness. Today, I finished my tenure. I shook hands with the last patient, put my stethoscope in my bag, spoke some parting words with my preceptor who has guided me in this overwhelming and intimidating foray into patient care. I really appreciate the chance I got to learn from these people and impose myself upon their lives. It's no small thing.

Monday, October 08, 2007

Saturday, October 06, 2007

Miniblog

http://indexed.blogspot.com/2006/12/medicare-dude-its-groovy.html

"An academically interesting disease is a disease in which there are more people studying it than there are people suffering from it."

"An academically interesting disease is a disease in which there are more people studying it than there are people suffering from it."

Friday, October 05, 2007

The Thing About Med Students

If you sit in any conversation with med students, you'll find that the topic of discussion is probably about med school. Our conversations revolve around study habits and how much we're procrastinating and how difficult that last test was and whether we've started thinking about the Boards and how much we like this or that professor and where the closest coffee venue is to the library. Oh, sure, we'll ask about each other's weekends or how the kids are or whether the weather will change, but we define our weekends by whether we studied or procrastinated and whatever the weather is, we will be dutifully napping in the library. (I admit, the married students with kids probably don't fall into the purview of this post).

Even when talking to my friends who are not medical students and not even remotely interested in medicine or science, I find that if unchecked, I will stray to our last anatomy lab or the weirdness of hantavirus or how behind I am in my reading. It's sad. I don't particularly like how I define my identity as a medical student and let medicine dominate my life this way. I have to always remind myself to maintain perspective, get a breath of fresh air, don't let a single thing - no matter how important or how fascinating - consume my entire life.

Even when talking to my friends who are not medical students and not even remotely interested in medicine or science, I find that if unchecked, I will stray to our last anatomy lab or the weirdness of hantavirus or how behind I am in my reading. It's sad. I don't particularly like how I define my identity as a medical student and let medicine dominate my life this way. I have to always remind myself to maintain perspective, get a breath of fresh air, don't let a single thing - no matter how important or how fascinating - consume my entire life.

Thursday, October 04, 2007

Someone's Already Said This Before

Wednesday, October 03, 2007

Distractions

Last week we had a dinner with our little sibs (first year students). It was fun; a decently large group of us went to a Korean tofu house. The food was good, the company was great. I really enjoyed talking to the first years. It's funny to be asked questions as if I actually knew something about medical school and how to get through it. I have no idea. No insight or wisdom to mine for here. But it's fun to interact with the new med students.

Tonight, a friend and I went to see a play downtown (David Mamet's "The Old Neighborhood") run by a nonprofit local theater company. It's strange to remind myself of the many wonderful things to do in the city. San Francisco is so incredibly rich in culture and art. Unfortunately, this year is proving to be busier and more stressful than ever.

Tonight, a friend and I went to see a play downtown (David Mamet's "The Old Neighborhood") run by a nonprofit local theater company. It's strange to remind myself of the many wonderful things to do in the city. San Francisco is so incredibly rich in culture and art. Unfortunately, this year is proving to be busier and more stressful than ever.

Tuesday, October 02, 2007

Monk

I don't know too much about the history of Myanmar (Burma) and there's been an information lockdown since the start of the pro-democratic protest. However, what I've seen and read has been absolutely shocking and unbelievable. What has happened to the Buddhist monks and their supporters is morally outrageous. This really strikes a chord in me. My thoughts are with them today.

Here is a poem I like:

Tour

Carol Snow

Near a shrine in Japan he'd swept the path

and then placed camellia blossoms there.

Or -- we had no way of knowing -- he'd swept the path

between fallen camellias.

Here is a poem I like:

Tour

Carol Snow

Near a shrine in Japan he'd swept the path

and then placed camellia blossoms there.

Or -- we had no way of knowing -- he'd swept the path

between fallen camellias.

Monday, October 01, 2007

Zoo Noses

Zoonoses are infectious diseases transmitted from animals. There are a lot of them and they are really random, but as I happen to like random diseases, they're pretty cool. Carriers can be pretty much anything, from cats to bats to fleas to sheep. Zoonoses include the common cat scratch disease and Lyme disease (both of which have been cases of the day) to really obscure ones like Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and psittacosis. I mean, who would think that you could get a disease from handling a sheep's placenta (Q fever)? Anyway, I just wanted to mention them because though memorizing the list kind of sucks, these weird diseases that I will probably never see have their charm.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)