Thursday, April 30, 2009

Decisions I

It's hard for someone who doesn't like to commit. But hopefully the next few posts will help me elucidate what I'm most curious about. Originally, I had favored a process of elimination but then I found the AAMC (American Association of Medical Colleges) website with 100+ specialties and subspecialties.

In looking at them, there are fields that I have or will get exposure that I'm interested in: Anesthesia, Critical Care, Internal Medicine, Cardiology, Infectious Disease.

There are fields that I have or will get exposure that I'm neutral about: Emergency Medicine, Hematology and Oncology, Pulmonary, Dermatology, Pain Medicine, Endocrinology, Gastroenterology, Geriatrics, Nephrology, Rheumatology, Neurology, Pediatrics (and its subspecialties).

There are fields that I have gotten exposure to that I don't think I'm likely to enter: Surgery (and its related cohort), Family Medicine, Psychiatry, Radiology, Radiation Oncology.

But for many fields, I won't get much of a taste; I'm ruling them out based on my likely false assumptions about these specialties. It's a shame, but we can't try everything. I don't think I'll get much exposure to or pursue: Allergy and Immunology, Genetics, Neurosurgery, Ophthalmology, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Sleep Medicine, Urology.

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

Pediatrics 110

I loved the attendings on this rotation, and the patients loved them too. Pediatricians are warm, enthusiastic, funny, and engaging. Oddly enough, I didn't jive with the "culture" of the residents. Every specialty has its own culture, and though there wasn't anything bad about the pediatric residents, I just didn't feel like I fit in.

Pediatrics has always been in the back of my mind as a potential specialty. During this rotation, I struggled a lot with whether I wanted to go into it; I would miss the adults, but if I went into internal medicine, I'd miss the kids too. In the end, I felt that the general bread and butter stuff didn't interest me enough, and I didn't feel like I fit into the pediatric resident culture. Though the "zebra" diagnoses (many of which are genetic) are fascinating, I'm not ready to commit to a pediatric subspecialty.

Monday, April 27, 2009

Poem: Were Sleep a Sound

Were sleep a sound, it'd be the caramel crack

of the crème brûlée, torched golden,

begging to be tapped by that silver spoon.

Not unlike a lake frozen once a year

calling for skaters, daring the brave.

That moment before we plunge into

the deep waters, the sweet custard,

that sweetness before sleep takes us

when you know you can't open your eyes

any longer, you fight a little,

just to see what it's like, struggle

in the arms of oblivion, half-hoping she

will take you soon to the repository of dreams.

What to watch today?

I can't remember what I saw yesterday

and I'm inclined to browse the flying section

or the unfinished dreams;

there's one in which I need

to return a stolen engagement ring,

and a dream in which I need to steal one.

Tell me of Ondine, that German water nymph

(the only German water nymph I know)

betrayed, hair a fountain, infuriated,

her long nymph finger pointed at this knight

cursing him to dread that divide

from this world to the next

never again to experience that break of ice

that crack of the crème brûlée

that falling into dreams I so covet.

Sunday, April 26, 2009

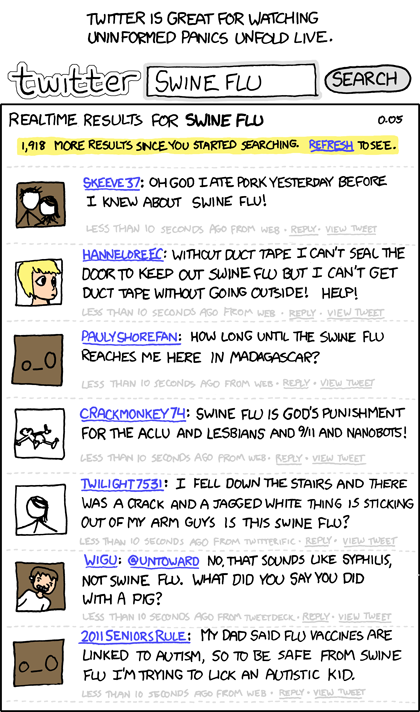

Swine Flu

Saturday, April 25, 2009

Urgent Care Reprise

Friday, April 24, 2009

Parents

On the other hand, I realized how central parental relationships and family dynamics can be to a child's health. Though rare, I've had parents argue and fight with each other and yell at their kids in front of me. Sometimes, a divorced parent will criticize the other parent and ask me to back them up. Those situations are awkward and difficult to finesse. I think it just comes with the territory of pediatrics.

Wednesday, April 22, 2009

The NICU

We don't get very much exposure to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) on our general pediatrics rotation. During my week in nursery, I got a little introduction to common problems seen in premature infants, surgical conditions, and the sepsis workup. It's a completely different world than well-baby nursery. Babies are in incubators, hooked up to ventilators, monitored around the clock. Everything is incredibly detail-oriented; even simple things like fluids matter a lot. A change of a few milliliters/hour of fluids in a baby weighing 500 grams (just over one pound) is critical. They have so many difficulties with respiration, immune function, temperature regulation, and other homeostatic mechanisms.

We don't get very much exposure to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) on our general pediatrics rotation. During my week in nursery, I got a little introduction to common problems seen in premature infants, surgical conditions, and the sepsis workup. It's a completely different world than well-baby nursery. Babies are in incubators, hooked up to ventilators, monitored around the clock. Everything is incredibly detail-oriented; even simple things like fluids matter a lot. A change of a few milliliters/hour of fluids in a baby weighing 500 grams (just over one pound) is critical. They have so many difficulties with respiration, immune function, temperature regulation, and other homeostatic mechanisms.I saw one newborn resuscitation. This was a baby at 34 weeks with known severe polycystic kidney disease. His kidneys were not only poorly functional, but also complicated the growth of his lungs (there was almost no amniotic fluid). The assessment by the neonatologist suggested that he might have a 50% or less chance of surviving his first few days of life. Unfortunately, the mother went into preterm labor. We were called to the delivery of this baby. This was so much different than the deliveries I had been at on my obstetrics rotation. The baby came out limp, blue-gray, and not moving. The neonatology fellow directed the resuscitation. With some warming, drying, and stimulation, he began to breathe spontaneously; his heart rate was around 80 (normal is well above 100). We then intubated him, putting a tube down his throat to assist breathing. We needed to secure access to blood and the residents began cannulating the umbilical artery and vein. Meanwhile, a respiratory therapist began bagging (hand-pumping) oxygen to the baby. He began to pink and his heart rate picked up. After getting access to the umbilical cord vessels, we drew up blood and handed it to the laboratory tech who was there (I was impressed by the team we could assemble at 10pm). He ran the samples on a portable analyzer in the room for arterial blood gases, blood count, and chemistry panel.

We then gave some surfactant down the endotracheal tube to help the baby's lungs open up. Things began to look pretty stable and we were preparing for transport to the ICU when the baby stopped ventilating. He began to turn blue, his oxygen saturation dropped from the 90s to the 80s to the 70s, and finally his heart rate dropped. Nobody panicked. The attending calmly took control of the situation. We began chest compressions, called a code (we realized we needed more nursing support), and the attending managed the airway. The fellow began listing the medications we wanted: epinephrine, THAM, fluids, blood. After suctioning a mucus plug from the airway, the attending reintubated the newborn and his oxygen saturation picked up. After ascertaining that he was stable, we transferred him to the intensive care unit.

This was the first time I'd seen an infant code. It's very scary and a little traumatizing. But I was impressed by the leadership of the neonatology team who seamlessly directed the resuscitation.

Image shown under GNU Free Documentation License, from Wikipedia.

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Well Baby Nursery

I had a great time last week in the well baby nursery. Our main goal is to learn the newborn exam. To be honest, prior to this rotation, I never really had much contact with newborns or infants, so this was a perfect time for me to get comfortable with babies, swaddling, crying, etc. The exam is fun. You can pick babies up, play with them, and do the same thing over and over. They're generally pretty cooperative (since they don't know what's coming). I got to hear a few good heart exams, a ventral septal defect and a persistent patent ductus arteriosus. Reflexes like the suck, grasp, and Moro (startle) are also fun. Learning about newborn rashes, parental teaching, and anticipatory guidance was pretty useful.

I had a great time last week in the well baby nursery. Our main goal is to learn the newborn exam. To be honest, prior to this rotation, I never really had much contact with newborns or infants, so this was a perfect time for me to get comfortable with babies, swaddling, crying, etc. The exam is fun. You can pick babies up, play with them, and do the same thing over and over. They're generally pretty cooperative (since they don't know what's coming). I got to hear a few good heart exams, a ventral septal defect and a persistent patent ductus arteriosus. Reflexes like the suck, grasp, and Moro (startle) are also fun. Learning about newborn rashes, parental teaching, and anticipatory guidance was pretty useful.One week is the perfect amount of time. It's fun to play with the babies, the hours are light, and they're cute (the fingers! the toes!). I also liked interacting with new parents with their apprehensions and aspirations. But the week was not too intellectually challenging. There are only a few well-baby nursery problems: weight and breastfeeding, jaundice, and, well, I can't think of much more (circumcision?).

We did have one particularly impressive patient. This was an eight hour old boy born at 41+ gestational weeks (induced because of post-dates). We put him on his tummy to look for any spinal cord defects (sacral dimples, tufts of hair) and he did the most amazing thing. He got onto his forearms, lifted his head to about 45 degrees and started looking around. That's at least a one month milestone! What a precocious kid.

Image is in the public domain, from Wikipedia.

Sunday, April 19, 2009

Poem: Nursery Rhymes

Nursery Rhymes

I never got why storks deliver babies

yet mother was a goose

For me, the mother of nursery rhymes

was dear doctor Seuss.

What kind of doctor was he

who conjured a cat in a hat

Three blind mice would lose more than tails

if they had to go against that.

Saturday, April 18, 2009

Dermatology

When I saw her, she was complaining mostly about mouth pain. Her tongue and lips were markedly swollen, she had erosions on her buccal mucosa, and she could barely talk or swallow. Her thighs had erythematous macules, 5-15mm with a few vesicles. Over the next few hours and next few days, she developed more lesions on her trunk and extremities, and they progressed to vesicles and bullae, and finally the pathognomonic target lesion with macular erythema around a vesicular or purpuric core. Indeed, this was Stevens Johnson Syndrome, one of the few dermatologic emergencies. In this disease, the epidermis sloughs off and it can involve large body surfaces. Patients often need to be treated like burn patients since they lose so much water through evaporation and cannot control their temperatures. Stevens Johnson Syndrome (and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis) also involve the mucous membranes; our patient had mouth and eye involvement. While Stevens Johnson Syndrome is often associated with medications, in children, it can also happen following a mycoplasma infection. Mycoplasma is a common organism in walking pneumonia. To test it, infectious disease drew some blood at the bedside, put the tube in some ice water and watched it coagulate. This was a cold agglutinin test, often positive in mycoplasma, and it was fun to do it right there to confirm our suspicion. The care was supportive and after a week and a half in the hospital, she went home.

Friday, April 17, 2009

Pediatric Medical Mystery II

The patient turned out to have a spinal epidural abscess. The radiologist read an extensive phlegmon extending from L1 to L5 impinging on the thecal sac with a septic arthritis of the L4-5 facet joint and a myositis of the paraspinous and psaos muscles. We were shocked. Spinal epidural abscesses are extremely rare, especially in a pediatric population. The risk factors are an indwelling epidural catheter and intravenous drug use, neither of which applied here. We were impressed by how extensive it was. It must have been encapsulated and growing as an abscess. Only when it broke open did the patient have meningeal signs and alarming laboratory values. We started her on ceftriaxone and vancomycin to cover staphyloccal and streptococcal species.

Neurosurgery came to evaluate the patient. At first they decided to do watchful waiting and not take her into the operating room. We also got neurology on board who suggested giving steroids to decrease cord compression. A blood culture grew out methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Again, we became the hub of all the consult services. Eventually, the patient did not improve on intravenous antibiotics. A repeat MRI showed worsening abscess and neurosurgery did a two level laminoplasty to drain the pus. When I visited her last she was recovering well post-op and her symptoms were improving.

Thursday, April 16, 2009

Pediatric Medical Mystery I

That turned out to be the right decision.

They were worried about a septic arthritis of the hip, one of the few pediatric orthopedic emergencies. When I evaluated her, she did not look sick and she was still afebrile. Her range of motion of the hip seemed to be limited by pain. She had external and internal rotation, limited flexion, limited extension. Her knees were fine. On examination of her back, she had exquisite paraspinal tenderness 1-2cm left of the lumbar spine. She did not want to stand. Her exam was otherwise unremarkable.

Our differential diagnosis was broad, encompassing toxic or transient synovitis, osteomyelitis, joint or peri-vertebral abscess, diskitis, lyme disease, Legg-Calves-Perthes, musculoskeletal injury or strain, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, stress fractures, rheumatologic diseases, abdominal etiologies, kidney stone, pyelonephritis. We decided to be conservative. We gave ibuprofen and consulted orthopedic surgery to rule out a septic hip. They didn't think it was a septic hip but suggested a bone scan or MRI of the spine to rule out diskitis or other infection. A bone scan would be easiest but would not show soft tissue well (which we were worried about because of the paraspinal tenderness). An MRI is expensive and requires sedation for a 6 year old. We managed to schedule an MRI for the following morning.

I love this stuff. The exciting conclusion of this case will come tomorrow.

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

Diabetes Management

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

Child Life Specialists

As adults and as adults working in a hospital, we often forget how scary such a place is for a child. We forget that the MRI makes loud noises yet requires a patient to stay still. We forget that we use technical language that children don't understand. But they are the patients and our focus must be on their well-being. Child life services provides the emotional and psychological support that they need. They can also provide educational services (contacting schools for homework, providing tutoring) and recreation for hospitalized children (including wii).

Monday, April 13, 2009

Poem: Violence, etc.

Violence, etc.

Red beads crawling ahead

white glows trailing behind

as I sail into the darkness

my feet dancing

to the voice on the radio.

Driving at night soothes,

collecting thoughts like alms

and poems like virtues -

appropriate, this Easter Sunday

my mind churning away.

Who can say how a stream

of consciousness tumbles

how I go from the resurrection

of Jesus to

the extinction of dinosaurs

(if one came back, we'd

call it lazarusaurus)

to giant meteorites and

robotic Japanese monsters and

global warming and

violence, etc.

Fog blooming over the city

a dew drop on rose petals

of a strange orange house

overlooking some obscure

part of this 280 drive home.

I always say I'll look it up

when I get back, but

I never do.

Saturday, April 11, 2009

Death of a Child

This patient was brought into the operating room where neurosurgery did a craniotomy, removing part of her skull to evacuate the blood. Unfortunately, the AVM was in an inoperable location and they were unable to clip it. Interventional radiology was also unable to put coils in it. Thus, the AVM could not be repaired and there was a significant risk of rebleeding. The patient was stabilized in the pedatric intensive care unit over several weeks.

Eventually she was transferred to the rehabilitation service. Over the course of three months, she regained the ability to walk, talk, and interact with people. Every morning, we would round on her, mostly to pay a social visit; she was adorable and we were incredibly pleased to see that despite this life-threatening episode, she was getting closer and closer to her baseline function. We planned to replace the skull flap from the craniotomy followed by radiation (gamma knife) as a way to reduce the AVM. Though we understood that her underlying structural defect had not been repaired, in our minds, she was a healthy child who had recovered remarkably.

Last weekend, overnight, she woke up with severe eye pain. The resident immediately went to evaluate her and consulted neurology and neurosurgery. Though initially her mental status was normal, over an hour, she slowly became obtunded and then nonresponsive. A decision was made to control her airway, and she was sent down to the CT scanner. Her AVM had rebled. The AVM, which had been precarious but stable for 4 months, had burst open. The neurosurgeons took her into the operating room but found that her brain was filled with blood. They could not stop the bleeding. Instead of letting her die on the table, they closed her up and brought her back to the pediatric intensive care unit. The following morning, her parents elected to withdraw life support.

I felt ambivalent about writing this. This is the second child I've seen die this year. It's tragic and it's frightening and it's serious, but those aren't necessarily reasons to blog. I think writing about this allows me to find closure to some extent. Coping is very difficult, especially in this patient who seemed to be doing so well, who we were so optimistic about.

For me, I was affected mostly by how emotionally wrenching this was. But for some of the residents, this sadness was compounded by guilt - could we have diagnosed this earlier? Could we have intervened? The chief residents held a debriefing session to discuss what happened. There was nothing that could be done; the AVM had such a brisk, voluminous bleed that no intervention would have saved her. Sending her to the CT scanner earlier would probably have lead to a worse outcome - having to code her in the scanner. All the right parties, neurology and neurosurgery, were involved and they did what they could. We were helpless to change this course of events.

My deepest sympathies to the patient, family, friends, house staff, and all those involved in this patient's care.

Thursday, April 09, 2009

The Danger of Spanish

I found that my interaction with him and his mother fell into the danger zone of Spanish. The last time I formally studied Spanish was in high school, and though I've been to Mexico and Argentina since, my Spanish is fragmented, rudimentary, and very basic. Yet I overestimate my abilities. I think I know what I'm talking about.

This is the danger zone of a language. If I knew nothing, I'd get a translator. If I were fluent, I wouldn't need one. But as I am now, I convince myself I can ask about fiebre, dolor de cabeza, tos, falta de aire, nausea, orina, etc. But I know I'm far from fluent. The solution is obvious; get a translator. Spanish translators are the easiest to get in the hospital. There are also less-ideal alternatives; we can get phone translators or staff who speak Spanish. But despite all this, I have a great reluctance to do so. I have no good excuses, and the only thing I can say is that I'm trying to recognize my limit and when I have reached that, I will get a translator. This is something I will continue to work on, and something I know will get more and more difficult in the future as I find my time more and more precious.

Wednesday, April 08, 2009

Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva

She was in her late teens, bright, outgoing, and engaging. She was, as far as I could tell, a normal high school student. She chatted about classes, friends, future goals, family, hobbies. She made it a point to live her life as normally as anyone else. And yet, her spine was fused, she had nearly no range of motion of one of her arms, her gait was a small shuffle, and her posture was fixed. She openly talked about her disease, acknowledged it as part of her identity, understood that few people had ever heard of it, and loved to share. I really enjoyed talking to her.

I was torn between two different emotions. We all know the prognosis of this disease; there's no cure, no treatment, and eventually bone will consume her life. And yet she was so optimistic, so full of life. She organized fundraisers for this condition, traveled to meet other patients with the disease, pursued big things. Even in the hospital, hope and cheer abound.

The other thing this brought up was the strangeness of Moffitt medicine. As a highly academic tertiary referral center, we see diseases that no one else sees. I love it. In some ways, it's not practical training at all; we get too used to the rare and obscure that we forget what the real world is like. But in other ways, it offers opportunities I can't get elsewhere. Meeting this patient was an extraordinary experience that I have trouble putting into words. Her attitude towards life in spite of her disease, her aspirations in life because of her disease, and her warm personality will inspire me for the rest of my time in medicine.

Tuesday, April 07, 2009

Poem: Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva

-

Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva

When I first wrote this, it was too locked in,

too myopic, too keen for details,

five wooden iambs, three horrid stanzas

as I imagined this poem must be,

trying to confront

the second most frightening

most perversely romantic

disease I've ever known.

This far out, who could say where the Gorgon was born,

writhing in clasps, a cave flung out to sea

the waves lapping at statues of rock, barren

and lonely, gulls in the distance.

Who could understand her plight;

she never asked for a lock of snakes

or a house of bones, she never asked

for a propensity for terror or

ophidian eyes; why,

she'd much rather let her hair down

without worrying about the hissing

and go out on the weekend.

You cover-judgers, she says, if only you'd--

and simply that silences her audience.

Take the Thinker, child of an august man

muscular, folded and brooding,

a marble-and-bronze sentinel

as if we would not take pause at the Gates of Hell.

What could force him into such a form?

Stunned as a new mother hearing the cry of her child

stunned as the backpacker at Iguazu falls

the toppling mists leaving rainbows in their wake.

Oh, the things one could contemplate in this world,

the passions and regrets that only spring to mind

when we can do nothing more,

villains and nemeses and lovers and loves

frozen in time, impotent.

Until I met Winter, who had a siren's voice

a music that rumbled in her chest

aching to escape an incarceration of bone.

Stricken by this disease of wayward romance

her muscle and fat ossify overnight

scaffolding bone on bone,

unpronounceable, unreasonable, unsolicited,

arresting her in this home she carries on her back.

Snail, turtle, armadillo, ankylosaurus,

if she spoke their language, she would ask

how they make their shells their armor

how they skirt that dreadful position,

elbows on tucked knees, Dante at his best.

If she spoke their language, she would ask

for a dance

a ballroom with three tiered chandeliers

chiming as a breath of air

billows curtains, billows ballgown

a step beyond this bony manacle

a spin past this bronze casting

a grin at the medusa that left her wallflower

for so much of the night because,

if we cannot have a last dance

what can we have, at all?

Monday, April 06, 2009

The Humanities

"In coming to understand anything, we are rejecting the facts as they are for us in favor of the facts as they are for someone else. The primary impulse of each is to maintain and aggrandize himself. The secondary impulse is to go out of the self, to correct its provincialism, and heal its loneliness. In love, in virtue, in the pursuit of knowledge, and in the study of literature, history, and philosophy, we are doing this."

Saturday, April 04, 2009

Cultures

On the other hand, I'm taking care of a child whose family recently immigrated to the U.S. Culturally, they are very passive when it comes to interactions with doctors. They grew up in a place where patients never argue with a physician and rarely speak up to ask questions or request clarifications. Through my entire interactions with them, they have treated me with quiet respect; they're always thanking me for my time and for my help. But I feel uneasy. They don't speak English, and though we use a translator, I wonder how much comprehension they have. Every time, I let them know that they can take control of their medical decisions, but I worry that their passive nature, while easy for physicians, will ultimately detract from the care they receive.